(The following article was written in February, 2005)

Jason Giambi had it all. And following the 2001 season, it was time to see exactly how much “all” was worth. Just one year removed from his MVP season, Jason was now 31, a free agent, and at the top of his game. He had developed the best strike zone judgment in the American League, and what he swung at he destroyed, slugging at a .660 clip. On top of that, he was a team leader, the heart and soul of the thrifty, upstart Athletics.

Due to Jason’s age and Oakland’s young talent base, there were probably better investments for the A’s money, including Gumby’s fellow infielders Eric Chavez and Miguel Tejada along with the big three: Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson and Barry Zito. But Jason’s time was now. And the A’s wanted to recognize that. The entire A’s payroll in 2001 was $33.8 M. The A’s are not a profitable franchise. But they wanted to reward their guy, and so they made a most generous initial offer: 6 years, $91 M. Jason’s salary, by itself, would raise the A’s team salary by 45%.

It was a damn good offer.

The A’s really couldn’t afford it, especially given Gumby’s burgeoning knee problems. We all envisioned Oakland having to eat the final two years of this thing. Giambi’s fielding wasn’t exactly helping his cause. He certainly would end up DHing before long. The Gumby who cares about riding motorcycles would have and should have taken it in a flash.

However, there was another suitor for Jason Giambi’s talents. For eighty-five years the New York Yankees have made a point of thieving talent from rivals. In the age of free agency, they no longer needed the addle-brained complicity of a fellow owner to do it. Almost immediately, the Yankees trumped. Over the course of the winter, the A’s would make six counter-offers (each less affordable than the last) and the Yankees bested them each time.

The Yankees are a profitable franchise.

In retrospect, the A’s could have made 100 offers, and the Yankees would have bested every one. Yankee Owner George Steinbrenner would later admit that he didn’t want Giambi so much as he wanted to deflate the A’s. And why not? Thanks to Moneyball, the Oakland Athletics had become the iconic baseball-success-on-ten-dollars-a-day franchise. Steinbrenner likes to buy his titles. To him, the A’s represent all that is evil.

One of the counters made by the Yankees that winter removed Gumby’s Steroid Clause — sort of a “this contract is void if you’ve destroyed your career with ‘Roids” kind of thing. It’s kind of spooky when you think about it; such implies both the Athletics and the Yankees knew Jason Giambi was juiced.

You know the rest: Big Gumby took New York for $120 M over seven (7) years; he was good, then he wasn’t. Now ‘Roids have destroyed his career and the Yankees can’t get out of the contract. The only way the justice could be more poetic is if the A’s had won something big without Jason in the interim. In lieu of such, cue up a Nelson Muntz’ “Haw! Haw!”

That’s not really where I want to go with this.

In the spring of 2004, while baseball was heating up, ESPN held a mock trial citing Competitive Imbalance as the issue. On the defense was the New York Yankees; on the prosecution was the rest of Major League Baseball, represented by Alan Dershowitz.

The Yankees franchise makes more money than any other, hands down. The Yankees have sources of revenue (including marketing and premium media contracts) that other teams do not have. While the A’s would be in the red at $75 M no matter what they did, the Yankees could spend twice that and still make a very healthy profit. And they do.

So ESPN brought together a bunch of people, held a mock trail, and asked if the Yankees have an unfair advantage because they can and do spend more money than other franchises.

The jury voted 10-2 that there was no competitive imbalance in baseball. Of course, the jury didn’t really say this. Several jurors mentioned how the Yankees are a symbol, and needed to be strong. Several pointed to the low-salaried Marlins winning the 2003 World Series and cited the law of averages: “It could happen, and did, thus it’s fair, right?” If you listened to these idiots, you get the feeling that what they actually answered was not “is there competitive imbalance?” but “does it matter if there is?” and they answered “no”. Resoundingly.

But they ruled there was no competitive imbalance; so let’s start there:

Really? No competitive imbalance? You mean to say the Yankees would have been just as successful over the past ten years if they hadn’t outspent every other team in the game by at least $200 Million? Steinbrenner really ought to hear that; he could save some dough.

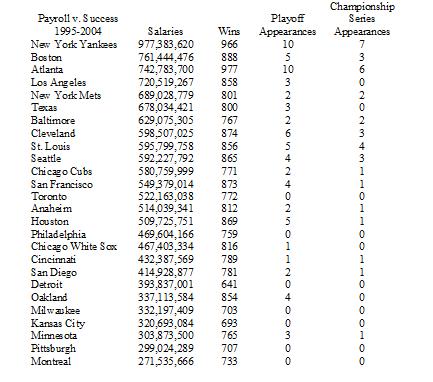

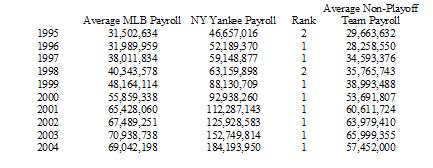

Here are some numbers:

I chose a ten year span, because 1) that’s what I had numbers for and 2) that’s exactly how long there has been an eight-team playoff format. The Yankees have made the playoffs in each and every one of the last ten years.

But there’s no competitive imbalance.

Does it disturb anybody else that payrolls have more than doubled in the past 10 years? Inflation hasn’t doubled other prices in that time. Our interest in the game hasn’t doubled, has it?

Try this one on: the average team payroll in 1988 was $11.34 Million. That was before the strike that cost us the 1994 season. Payrolls have increased six hundred percent since then. I never would have considered the José Canseco/Mark McGwire Bash Brothers a time of innocence and naïveté in baseball, would you?

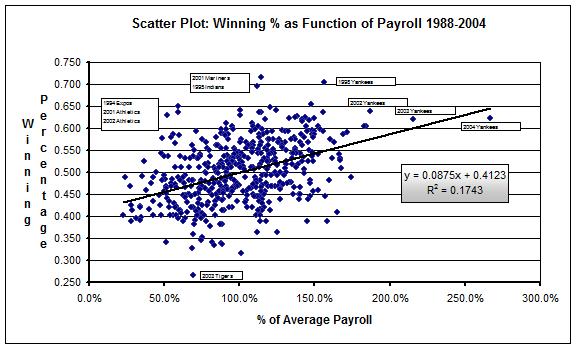

The above is simply a graph of payroll vs. winning percentage. I’ve included a “best-fit” line –statistically generated—and labeled some of the more notable points. If money doesn’t matter, that line is flat. Note the R-squared value. That value represents how true any given point is to the trend. The value is always between 0 and 1; the closer it gets to one, the more true the fit. 0.17 is not a good fit, and THANK GOD it isn’t or I’d never watch baseball again. If a low payroll necessarily dictated a losing season, then what’s the point?

The trend, however, is clear, is it not? The higher the payroll, compared to average, the better your team will perform.

But there’s no competitive imbalance.

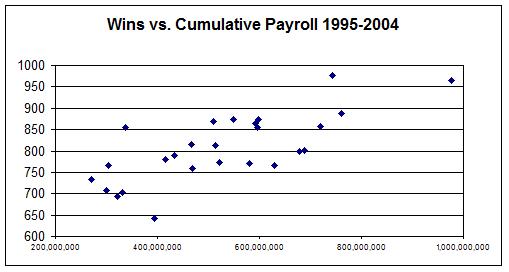

Many of the points on the above are misleading. Teams pay for yesteryear all the time. Big contracts get eaten. Let’s look at bigger picture stuff:

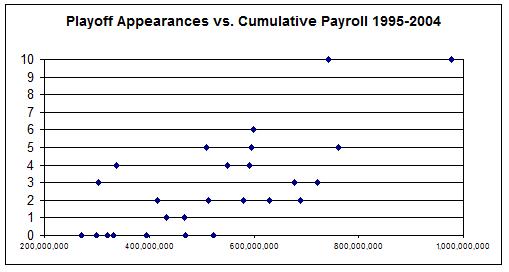

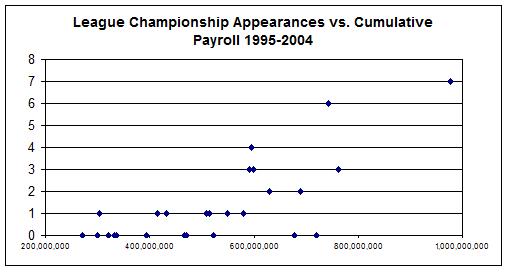

See if you can pick out the New York Yankees dot on the next few graphs:

Here it is, flat out: what you paid and what you got over the past ten years. The Atlanta Braves actually have the high-water win mark, but they don’t stray from the imaginary best-fit (not shown here) line much, do they?

Two notes: The Diambondbacks, Rockies, Devil Rays and Marlins have been removed from these graphs for obvious reason. The R-squared value for this best-fit line is 0.54.

But there’s no competitive imbalance.

Nope. No competitive imbalance here.

Let’s look at those darn Marlins. They’re so smart. They were the impetus for the entire defense argument: gee, the Marlins won the Series, while paying a bargain basement $48,750,000 on salaries (25th in baseball). Therefore, I’m just bitchin’ about nothin’, right? Anybody can do it.

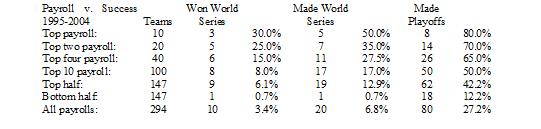

Lessee, the 2003 Florida Marlins entered the playoffs a Wild Card with a 91-71 record. In winning the 2003 World Series, they became the first “lower half payroll” team to do so in the era of the eight-team playoff. Looking further: Since 1995 began, there have been 294 “seasons “ of baseball (one for each team for each year). Naturally, 147 of these seasons have been in the top half of payroll, and 147 in the bottom half. Of the 147 in the bottom half, 18 have made the playoffs (12.2%). That’s more than I would have guessed. (27% is average); that stat gave me some hope.

Now, of those 18 teams, exactly two (2!) advanced past the first round. Those were the 2003 Marlins and the 2002 Minnesota Twins, who advanced exactly one round by beating another of the 18, the 2002 Oakland Athletics. The Twins were then soundly defeated by the eventual champion, the Anaheim Angels.

So, in ten years, in 147 seasons of lower-half baseball, there has been exactly one (1) unqualified success story. At least it was no fluke, right? The Marlins clearly overwhelmed the competition, right? They didn’t rely on random idiocy like Gold Glover José Cruz dropping a routine fly to advance past the Giants; they sure didn’t need one of the most notable cases of fan interference in baseball history to beat the Cubs; nor did they rely on a rookie nobody’d ever heard of to mow down the much favored Yankees. Why, the Marlins were clearly so far from a fluke that they very nearly came with five games of the playoffs the next season.

1 in 147. But there’s no competitive imbalance.

OK, OK. So there was competitive imbalance. What’s the point? Who really cares? I mean, seriously — 10 of 12 jurors certainly didn’t have a problem with Yankee dominance. Why should we? At the end of the day don’t we say, “if the Yankees make millions more than their opponents, what’s wrong with spending more on their product?” Isn’t America about having the integrity to invest in your company? Doesn’t that deserve accolade, reward?

After all, we don’t think McDonald’s should yield their Super Bowl ad time to Bob’s Big Boy out of the spirit of fairness, do we? And, in that spirit, we clearly want to chide the penny-pinchers. Look, you Kansas City Royals, if you can’t invest a few damn dollars, you don’t deserve to have a strong franchise, do you?

The difference is this: nothing in baseball happens outside a vacuum. No double hit isn’t also a double surrendered. No run can be scored without a run given up, and no game can be won without a game being lost. If Bob’s Big Boy goes out of business, McDonald’s will benefit. A certain percentage of every would-be Big Boy burger dollar will go to McDonald’s instead. If the Kansas City Royals go under, however, that isn’t necessarily good for the Yankees. It’s one less team that the Yankees can judge themselves against; it’s a wonder of “where are we going to get those six wins per year, now?” Expansion teams aren’t quite the pushovers they used to be.

I wanted this essay to be about whether or not Yankees overindulgence was good for baseball. In exploring that question, however, it became impossible to tell. What does “good” mean? More attendance, I suppose, is a “pure good”, just as a strike is a “pure bad” But what else is? Do we want thirty 81-81 teams? Of course not. Do we want a different team to win every year? I’m not sure that’s necessarily a good thing, either.

In ten years, the New York Yankees have spent almost one billion dollars on salaries. No other team has come within 20%. Doesn’t that just seem wrong? Is it good that salaries have increased six-fold since 1988? I find the overblown salary stuff akin to steroids themselves: in a closed universe, some are playing by different rules than others. Doesn’t that seem wrong? The Bud Selig era is replete with this “see-no-evil as long as the dollars are flowing” crap. . And does it surprise anybody that the Red Sox, the Yankees chief rival, are #2 on the spending chart?

So the question remains, is it good for baseball when the Yankees spend millions more than any other team? Honestly, I don’t know. I don’t know anymore than I know whether or not inflated salaries have been good for baseball. It seems bad, but is it really? I think you could write a book on the subject and not come to a definitive answer.

Hence, I return to Big Gumby and his Big Fat Contract. Who was this contract good for?

The Yankees? Clearly, no. They’re trying to get out of it.

The A’s? Well, they certainly saved money, but they lost consecutive playoff series by one run a piece following Gumby. Think he might have helped some?

A’s or Yankees fans? No, you’ve pissed us both off.

Baseball fans? Why, you’ve had the privilege of witnessing the Yankees indulge in their unbalanced universe and then have the audacity to complain how they were cheated. Yeah, we’ve all enjoyed that.

The players union? Salaries, in general, have risen since the Gumby deal; that’s certainly true. However, 2004 marked the first time in the Free Agent era that team salaries declined. Did Gumby’s deal do that? Probably not. It’s probably the Moneyball crowd that lit that fire. But what was their incendiary incentive if not contracts like Jason’s.

This winter, Carlos Delgado was a free agent. Carlos is among the most feared hitters in the game; he plays First Base, but not well, like Jason. Potential injury is a concern with Carlos, like Jason. Carlos is 32, just one year older than Jason when the latter signed with the Yankees. Carlos is one year removed from an MVP runner-up season. Should I go on? Looking blind, I think I’d rather have Gumby in 2002 than Delgado in 2005, but it’s close. There were four suitors for Carlos’ talent this winter. One was a New York City team (the Mets).

Carlos Delgado signed a contract for less than half what Jason Giambi signed for in 2001. And Delgado’s contract has a steroid clause. Tell me Jason Giambi hasn’t left his mark on deals like these.

Jason Giambi’s contract has been good for exactly one person: Jason Giambi.

And so, here’s the $64,000 question: Is the Giambi contract typical or a-typical of that which the Yankees do on a repeated basis. Jason Giambi, Alex Rodriguez, Catfish Hunter, Ed Whitson, Derek Jeter, Mike Mussina, Reggie Jackson, etc., etc…are these signings similar or dissimilar?

If you go with “similar”, I think you have to conclude that what the New York Yankees do with their money is, indeed, bad for baseball.

Right now one thing is very clear: Alan Dershowitz should stick to the defense.

Sources: www.mlb.com, www.espn.com

The Moneyball review can be found here